The phrase picture logic has been like a fly buzzing in front of my eyes for the last few weeks and linked interestingly to a Paris Report.

I was recently listening to Tim Goodman of The Hollywood reporter discussing the rise of directors in television and how show runner/writers were reacting against this.

Graham Yost (Justified, The Americans, Sneaky Pete, etc.) recalled first seeing that unique framing on Mr. Robot and thinking, “That’s interesting. Please don’t do that again.” (Goodman, 2018).

The rise of the auteur TV director. The point under discussion was how this visual style and weirdness often got in the way of the story.

But yeah, that description to a bunch of series writers didn’t go over very well for one simple notion that has been true forever: Television should be about the story, as written. (Goodman, 2018).

This argument reminded me of the kind of reaction that other art forms have experienced when the perceived wisdom and status quo were challenged.

At another point reference was specifically made to Twin Peaks “Twin Peaks was all about the freaky, not the story” (Goodman, 2018). David Lynch was the film maker that first cracked the door to alternative narrative structure for me, the cyclical structure and logic of Lost Highway was so strange, on first watch it was frustratingly opaque, I left the cinema angry. I’m sure Lynch would have been pleased at that.

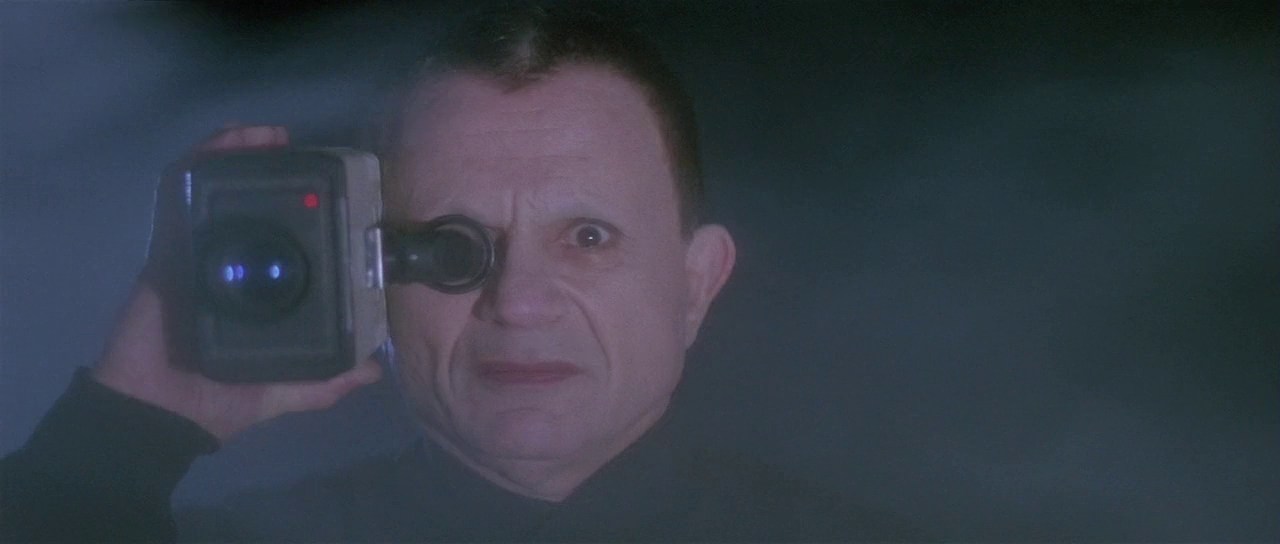

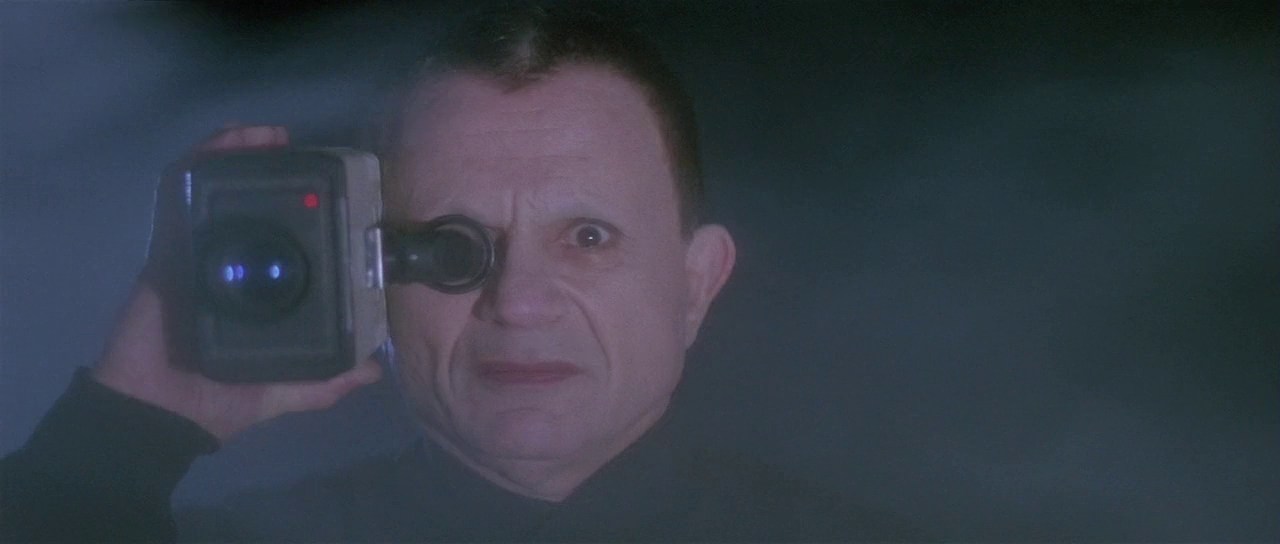

I’m still not sure that I understand what Lynch wants to say with it but I can take a journey with it, a road movie that has no destination. For me the video tape, Noir genre elements, and actor/character switches begin to question image obsessed culture, and gender roles and values in a rapidly changing society.

Lost Highway (Lynch, 1997)

There is more TV than ever, too much to watch, is this not precisely the moment when a plurality of voices and approaches to mass media should be allowed to question the role of screens, their power and our relationship with them. Picture logic rather than word logic. Links between the work of Lynch, Surrealism and Dada have been made regularly. Lynch’s work is terrifying, irritating, funny and it breaks the formal rules of story telling and film-making. I once heard it joked (sorry I don’t remember were) that every art gallery in the world has a copy of Fountain by Marcel Duchamp (1917) but some of the have just put it in the wrong room . It might be argued that you don’t even need to see Fountain in a gallery to experience it, it is so ubiquitous that it reminds you of its existence in every bathroom. There are issues of gender in this statement, only male bathrooms have urinals, but there is still an interesting question made by Duchamp about the importance of materials, artefacts, and skill in the status of a work of art. Was it subversive because it was absurd and funny?

(Duchamp, 1917, replica 1964)

Fountain as a ready made can ask these questions to a wide audience, its message is accessible, a viewer does not need a significant amount of art education to understand that calling a toilet art asks some big questions about art, questions that a lot of casual art goers are probably asking anyway. Cinema and television are to me interesting art forms because of their popularity and reach, TVs sit in a large number of the homes on the planet, I see this as having a huge potential for distributing ideas, asking questions, but a viewer has to choose a show, not become disengaged or switch off from it. There is a fine balance between pleasure to the eye and pleasure to the brain. I would argue that that the combination weirdness and visual flourish in Auteur led TV, like Twin Peaks, could provide not only an interruption to the status quo but also double hit of eye-brain pleasure.